Cannon Fodder’s Chaos—In conversation with Canyon Castator

Canyon Castator, The Interventionist, 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 64 x 115 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“At its core, Cannon Fodder is a condemnation of the glorification of violence while existing inside of it. It’s a bolt that’s become self-aware of the far more sophisticated machine it serves, bearing witness to its own hand in keeping the engine running—a 2-stroke engine powered with a perfect mixture of pleasure and fear.”

—Canyon Castator, 2025

Canyon Castator’s canvases erupt with jagged cultural archetypes in hyper-saturated color, featuring sardonic figures that announce themselves in ultra-excess. By synthesizing digital and traditional techniques, he produces large-scale, chaotic paintings where disturbing imagery, fractured American mythologies, and personally pivotal moments collide. I first encountered his hilarious, biting, and daredevilish work at Postmasters six years ago, and his practice has only grown more audacious since.

We met in person for the first time in February 2025 at Mohilef Studios in Los Angeles, just weeks after the catastrophic California fires had forced his young family to evacuate. The eerily quiet aftermath that settled over the city colored our conversation, as Castator prepared Cannon Fodder, an ambitious new body of work grappling with the absurdities of US spectacle, masculinity, and militarism (to name just a few themes). Though still unfinished, the paintings already carried a seductive charge through layers of oil, acrylic, and airbrush—a preview I felt privileged to glimpse, and one that made it clear the show, which ran at Mohilef Studios in conjunction with Diane Rosenstein Gallery, would be nothing short of intoxicating.

We spoke about the challenges of parenting in moments of crisis, modern-day masculinity, and the growing community taking shape at Mohilef Studios, which hosts seventy artists across its two buildings, as well as exhibitions. Castator was candid about his formative mentorship with Karen Wong, the imprint of childhood media on his worldview, and his layered process of translating drawings into monumental, painstakingly finished canvases.

The following interview was conducted in February 2025 at Mohilef Studios in Los Angeles, California

Angelina, Indigo, Canyon in front of Long Hollow Loop, 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 80 x 60 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Clare Gemima: Before we talk about your work, are you and your family okay?

Canyon Castator: When the fires happened here, we were in an “evac” zone, but luckily our house was fine, and so were our neighbors’ houses. There was a severe amount of smoke and debris right over us, and we had to wear masks. We decided that Angelina and Indigo would go to New Zealand and stay with my dad for two weeks.

CG: Ah, great idea. Where did you go? What did you do?

CC: I spent a lot of time unpacking and assembling air purifiers (we now have four of them), cleaning air filters, and sweeping residual dust and debris off the house and surrounding areas.

CG: And where did your dog Birdie go?

CC: Birdie? She’s my ride or die. She was with me the whole time.

CG: I guess you also had to stay here and prepare these paintings.

CC: Yeah. Well, initially I thought okay, I know that the beancounters that work for Frieze are going to make the fair happen—they have to—but there was also a lot of talk that it would be called off. If Frieze doesn’t happen, then our Mohilef open studios won’t happen. If that were the case, why would I put on Cannon Fodder?

CG: I assumed that Frieze would be canceled. What do you think about the fair continuing? Do you find that problematic or charitable?

CC: The show must go on. They hired a PR team and found a way to, you know, virtue signal their way through it, and align with the “right” initiatives and organizations. It’s such an economic titan. People who live in LA are relying on business continuing—not just art people, but everybody. So when it comes to something like Frieze, there’s so much money involved, not just for artists and galleries, but for art handlers, shippers, and vendors, etc. These people are all relying on income, so it’s good that it’s happening.

CG: Waste trucks, toilets… so many other aspects are involved too.

CC: Capitalism never really leaves a great taste in one’s mouth when considering the aftermath of a natural disaster. It’s just a necessary evil to believe that if there’s money moving around it will make life easier. I’ve spoken to numerous artists that are relying on Frieze because they’re basically screwed otherwise. The city has been eerily quiet since the fires, so best case scenario is that the fair brings back some energy.

CG: How many artists are in each of the 2 Mohilef studio buildings and what’s the science behind your selection process?

CC: Just over 35 in each, so 70 in total. And artists apply or are recommended. We ask to see their work and after that we meet and tour them through the building in person. I usually try to conduct these tours myself, but sometimes they are led by other studio artists. It’s very organic in a way. We really just want to keep it a space for artists. Serious artists.

CG: Different topic, but I am curious about how having Indigo and becoming a dad has shifted your practice?

CC: I think being an artist in and of itself is a selfish act, right? The things that we think about in general are very focused on our own myopic perception of the self. All of my work somehow was very much about me and my interests, and in the moment of the here and now. As I think more and more about the idea of having a son and bringing a so-called “man” into the world… I don’t know where to begin. It’s just absolutely wild. I think masculinity is going through this insane identity crisis right now too. I want to celebrate this fascinating period of having a child, one that is going to have to somehow navigate his way through that crisis. It’s really brought my attention back to thinking about things that I was exposed to and gravitated toward as a kid, and how it shaped the way I experience the world. Everything from the media, to the way I was taught “goodness” as a boy. As I was growing up, it found itself within the context of super-hero comic books and cartoons where there’s seemingly always a good guy and a bad guy. These sorts of dualities were always very clear and understood. This idea of heroism, honor, and pride were virtues that had to be protected at all cost. I mean in hindsight it is all super fucking weird. I feel like it also primes kids to be pro-patriotic, or indoctrinates them into eventually providing service to their country. I don’t know. It’s all so loaded, and hard to digest.

CG: It’s also crazy to think about how Indigo will grow up and navigate the school system once he enters that.

CC: For sure, I hated school. It’s something I wouldn’t wish upon my worst enemy, but of course I’m sending my son. I can’t imagine that public schools in America have improved much in the past 30 years either. Becoming a father has inevitably shifted the way I consider structures of influence—how value systems are formed, reinforced, and quietly inherited. As I look at the earliest mythologies that shaped me, I find myself retracing the architecture of indoctrination embedded in so much of the media we offer to kids—cartoons, comics, movies, video games—packaged as entertainment, but loaded with ideological scaffolding beneath the surface. This body of work is an attempt to map out that apparatus—to lay bare the ways mass media uses spectacle to instill foundational ideas around power, virtue, and violence, particularly in the imagination of young men. Historically, the most weaponized and expendable resource in the history of human warfare has always been the young, and the process of priming that demographic starts long before anyone enters the battlefield. Stories of heroism and self-sacrifice become vehicles for grooming, often dressed up in the language of morality while ultimately serving as a sinister utility. I don’t see my paintings as external critiques. If anything, they are self-implicating. I’m not positioning myself outside of the system—I’m evidence of its effectiveness. I fucking love a video of a car crash. I’ll watch a football game, or a Marvel movie in theaters. This is the media that shaped me, and now I’m trying to understand how much of that internal architecture will inevitably filter down to my son.

Work in progress for Cannon Fodder early 2025 at Mohilef Studios. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CG: So as I’m standing here in your studio, I’m seeing tanks, halos, devilish beasts—and even Spider-Man figures spread across five large canvases. It feels like I’ve walked smack bang into the middle of Cannon Fodder in the making. Some look more finished than others… Are they all currently in progress?

CC: No, not quite, two are already finished. Basically, all of the parts on the canvas that are still white are the final parts that need attention. I generally mask off an area, isolate it, cut it out, paint it, and then it’s done. I try to utilize different approaches and visual languages for each element that aligns with its unique subject matter. It’s kind of like a reverse-collage method.

CG: And you’re using airbrush and acrylic?

CC: Airbrush, acrylic, and oil paints.

CG: It’s so amazing to see these in person. I remember first seeing your work at Postmasters in Tribeca. It must have been early 2019. I then read more about you, and learnt that Karen Wong served as a sort of mentor to you at some point?

CC: Yes. At the time she was the deputy director of the New Museum. She was a hugely important mentor to me, and a great friend. We met coincidentally. I had a friend who was interning at Storefront for Art and Architecture, and Karen was on the board. She’s always had important titles. He introduced me to her over lunch and I showed her some of my iPhone drawings. We became fast friends after that.

I didn’t grow up in New York, so I had literally no idea how these types of things, or random meetings really worked. I got lucky.

Canyon Castator, Installation of Infidel, 2025, at Postmasters, New York. October 19–November 30, 2019. Photo courtesy of Postmasters.

CG: Where did you grow up?

CC: Colorado. Well, Texas and Colorado. I mean Colorado is special in a sense, but it’s not a place for artists to become…

CG: established?

CC: Yeah, I don’t know. There was no interest in pursuing or understanding contemporary art or culture there. More like a lot of conversations about hiking and stuff. Once I met Karen, she took it upon herself to formalize a crash-course on art via exposure. She’d say,

“We’re going to go and see this show, we’re going to go and see that show, I want you to see this, this, this, and this!”

CG: That’s so incredible. I am hopeful that people like that still exist in New York—the types that take you under their wing so generously and with no hesitation—especially in a field as tough as the one we’re in. Does she come and visit the studio?

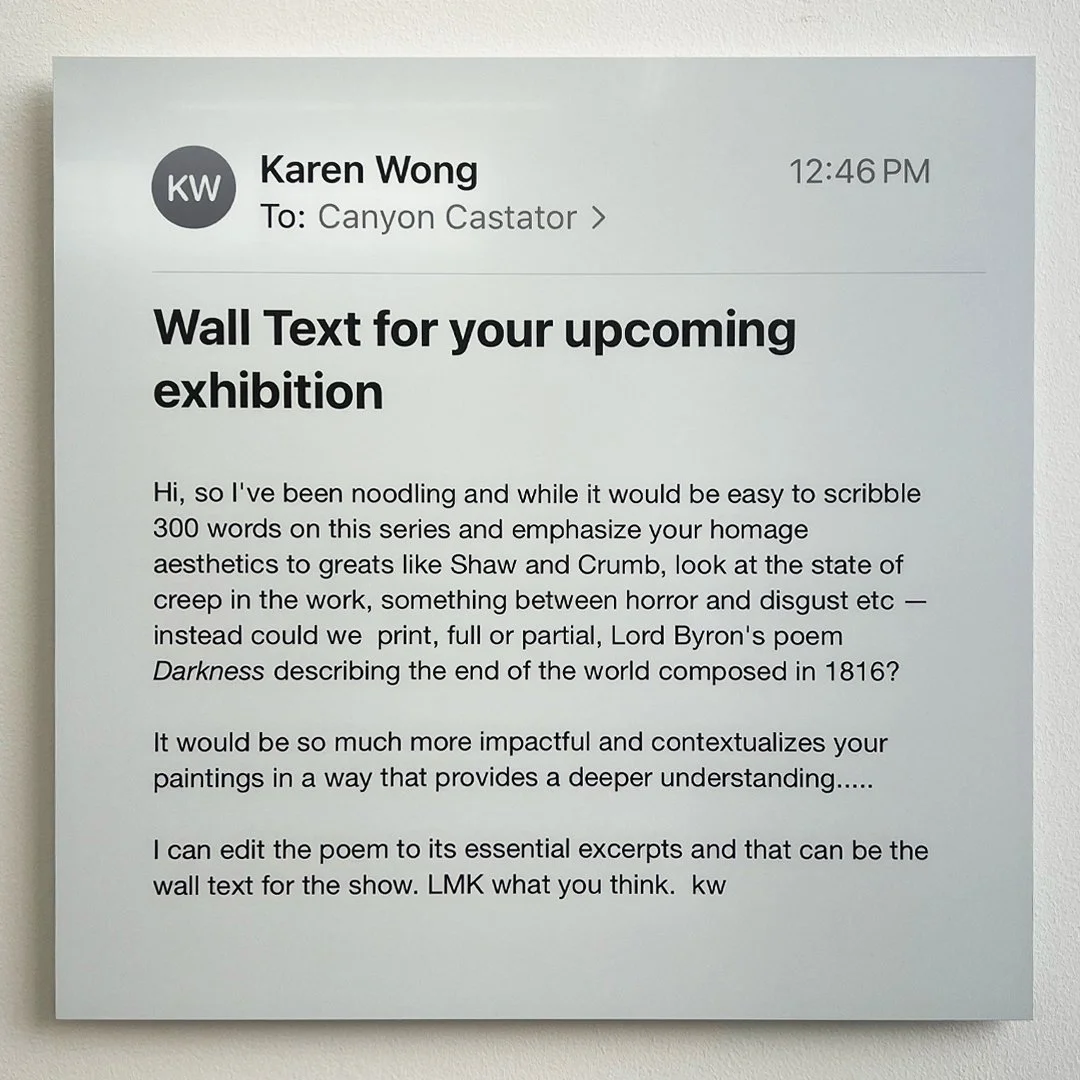

CC: Yeah, when she’s in Los Angeles. She’s seen this body of work, and we’ve talked about it. She’s quite literally watched every stage of my career from the very beginning when I was learning how to paint. She’s watched me make some horrible, some good, and occasionally great paintings here and there. She’s always championed exploration in the work, and to push it. She actually wrote the exhibition text for this show. Want to read it?

CG: Sure.

CC: This is it. Very short and sweet.

CG: “State of creep”... wow.

CC: She didn’t know this was going to be the text I’d use, but she sent me this email this morning. I screenshot it and I sent it to my printer.

CG: *Laughs* I like the open-endedness of it, and the length. This is the official text for Cannon Fodder?

CC: I like it, so yeah. Have you ever read the poem?

CG: Lord Byron’s Darkness? (1816). No. I haven’t.

CC: It’s great, but fucking dismal.

CG: Would you describe your paintings as dismal?

CC: I think there’s a lot of underlying dismal subject matter, especially once you start picking apart the work. Underneath these bright cartoony surfaces, the meat of it is dismal but addressed in a sardonic way in an attempt to make it consumable.

CG: And you’ve got these sorts of American flag-wearing pro-military, Teen-Mom, and Tomb Raider-esque characters too.

CC: Yeah, they’re a part of the hyper-masculine visual vernacular and…

CG: don’t want to say zeitgeist… but zeitgeist.

CC: I mean, it rings really true right now, this huge swing towards this awful, ultra-masculine, you know, red-meat-only diet, “fuck feminism” dialogue. The proclamation that men want a subservient wife. This sort of creatine gym, bro-podcast type culture—all of that. I wanted to pull the rug out from underneath these characters. All of the ones you see in these paintings are archetypes of things that are quite disdainable, but they’re also absurd and laughable.

CG: And sometimes they’re actually quite beautiful.

It’s those contrasts that make your work so intense—there’s all this vulgarity crammed into the canvas, that you have somehow made so gorgeous and digestible. The colors you work with are extremely oversaturated and arresting too. It’s easy to get lost in all of your details, and you can’t help but want to dissect every inch of your canvas, but somehow that only pulls you into a weird, paradoxical conflict.

Are all of these works part of a larger series, or do they act as more singular pieces?

CC: There was a bit of a linear 5-chapter-novel intention to making them. It starts with the wallet family photo. That’s my wife Angelina in the center.

Canyon Castator, Long Hollow Loop, (The Wallet Photo), 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 80 x 60 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CG: Was the wolf inspired by Birdie?

CC: No, I am the wolf, and Birdie is the vulture. I lived in a trailer park in Texas, which lends itself to the work’s quite personal background. The sky is a scorched, really ominous yellow. It feels like a moment captured before one of the characters is shipped off to war. Something unpredictable is definitely about to happen. It shows a connection before a separation of sorts. I don’t know, there’s an unsettling idea of the family photo, for me at least. We put on our best face for a family portrait, yet life continues to be very unexpected.

Canyon Castator, Cannon Fodder, 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 96 x 64 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CC: And then there’s this painting, Cannon Fodder*, a chaotic, marinated-in-militia landscape. A wartime painting that broadcasts just how fucking ridiculous war looks. The main character has two sides to it, almost like a set of angel wings coming off his back. I wanted to depict the weapons war is waged with on one wing, and this sort of propaganda machine on the other. Using foxes seemed literal enough to explain itself.*

CG: And there’s a more hyperrealistic rendering of a soldier wearing a helmet, floating next to a very Grand Theft Auto styled bikini model?

CC: Yes. I didn’t want to land on any specific way of rendering because jumping between various ways of portraying characters keeps it interesting for me.

CG: Seeing as you work with so many different illustration styles, how do you decide which ways to render certain characters?

CC: Well, with the men, I grossly exaggerate this stupid kind of muscular high-testosterone fantasy—an extreme end of the masculine spectrum. Some of the female characters are based off found images I use as source material, whether found in a video game, or in propaganda used directly or indirectly to lure people into joining the army.

CG: At the beginning stages, when you start to build the composition, how pre-planned are you?

CC: Incredibly.

CG: I can imagine it’s quite meticulous.

CC: So, I’ll actually show you how I started one of these. I draw them on an iPad, and I just play with different characters in the composition.

CG: This is Procreate?

CC: Yeah, it’s just Procreate. Little kids use it now, but I’ve been using it for so long that when I first got it, I felt like I was the only person utilizing it. As if I alone had some secret, sacred tool.

CG: So you have all of your characters uploaded ahead of time, knowing who will feature in certain paintings?

CC: No, not necessarily. I make tons and tons of individual drawings and pick and choose from an index of characters.

CG: So there’s no real risk factor once you translate the work from digital to physical?

CC: I think I cycle through a lot of risk factors through the drawing process. There’s so much thinking surrounding the painting’s composition and content, and it’s intentionally separate and detached from the physical painting process.

Once I am finished with the composition, I then translate them directly using a huge flatbed printer. I design this truly insane journey for myself in the drawing process before I set out to actually paint them.

CG: I was going to ask if anything was printed…

CC: All of these black lines are printed. You can see the difference between the black which is printed, versus the black that I have painted. I don’t know if anyone else would notice that, but I do.

CG: Because society has become so familiar with Photoshop and graphic art, I can imagine some of your audience assumes all of your work is printed.

CC: If they don’t see them in person, for sure.

CG: But I guess that’s also part of what makes your work translate so well digitally, which is no small feat at all.

CC: They’re pretty authentic. I started painting with such an awareness of how things looked online, but I go to extreme measures to make my work worth seeing in person. Worth driving across town to look at in the flesh.

Canyon Castator, Cry Havoc And Let Slip The Dogs Of War, 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 90 x 90 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CG: Your work would be near impossible to photograph in a way that would show how complex and rich your textures are, as well as the unexpected ways you embrace imperfection. Did you study painting?

CC: No, I didn’t graduate high school, but when I was living in New York, Karen Wong introduced me to Tal R, who was teaching at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. He invited me to be a guest student. I was there for maybe six months.

CG: Woah, you were trained formally there?

CC: Not really. I learned how to talk about painting in Düsseldorf, but when I decided that I wanted to learn how to paint in oil, I took lessons at the Art Students League in New York.

CG: Why was it so important for you to introduce oil paint?

CC: I felt deeply insecure about not having grown up around certain art materials, nor having any understanding of how to work with them. I thought that the first instinctual thing for me to do was to try honing a craft or skill that was impressive regardless of what sort of subject matter I wanted to render. I could then understand that a painting could be made very well (even if it was an objectively “bad” work of art). I also wanted to hide behind the ability to render a face, or paint a figure well, and that was such a ripe learning experience. I eventually unlearned all of that, but it’s still there. Everything you see here is delivered 100%. There’s an immense amount of control and reasoning behind each and every aspect of these works. There’s so much freedom in that. I feel it’s...

CG: the freedom that comes with knowing how to execute?

CC: Yeah. But of course there are still moments where I don’t know how to do something, and that’s when I leave the material to do its own thing, create its own environment, and be very open to not forcing anything to happen. Why torturously spend a whole day painting mud when I could rely on sand and sawdust mixed into the paint to create surfaces that look and feel so much more organic. I use all sorts of materials, and although I’m not the best at airbrushing, the sorts of contrasts that can be created between having a donkey painted with oil juxtaposed with a breast that’s airbrushed with very soft, smooth, and perfect highlights is what I like. The ability to create those sorts of tensions between vastly different application methods is important to me.

Canyon Castator, detail of The Interventionist, 2025, oil, acrylic, and ink on canvas, 64 x 115 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CG: But these sorts of decisions happen only once you’re at your canvas?

CC: Yeah. I ask myself what I would have to do in order to make the illustrations come to life in the most interesting way, or somehow link it back to, or sometimes differentiate itself from its original source material or idea. It’s good to have a large Rolodex of techniques to choose from.

CG: What a massive undertaking. It seems as though it would be extremely difficult to combine so many different techniques as seamlessly as you have.

CC: You think so?

CG: I can just imagine it being so overwhelming, even anxiety inducing in some crucial stages.

CC: Yeah. I look back at the paintings that I made for my first Postmasters show in 2017 and I see such a huge appetite—I was super hungry. I look at some of the characters I used, how I placed them sitting on top of, or next to each other, and realize how much better I have become at certain things over the last eight years. I mean, I still end up doing some things twice or three times to make it work.

CG: So these works take quite a long time to make?

CC: It’s changed over time, but I’ve been working on the pieces for Cannon Fodder for roughly eight months.

CG: Other than canvas, have you tried to paint on any other types of substrate? What’s been the least successful sort of introduction of material to your work?

CC: Working on aluminum.

CG: It just didn’t take?

CG: It didn’t at all. The paint would dry too fast. I would mask off a little area that I was going to work on that day, but once I was ready to peel my tape off everything that was underneath it would lift—even the gesso. I would have had to completely change the way in which I paint in order to work with it. But I really love working against the bounce of the canvas. I’m literally cutting on its surface with a razor blade and roughing it up constantly. I appreciate how resilient and tough it is.

CG: Do you get much time to look at paintings and sculptures, or visit exhibitions happening in the city? Do you feel like you need to do that while you’re working in your studio?

CC: It really depends, but I think so. If I lived in New York, it would be a bit different.

CG: I’m curious about whether you find that helpful, or more of a distraction?

CC: I think it’s super helpful because oftentimes artists who do one thing over and over again do it really well. They’ve mastered a technique, and if I can spot that, I’ll try and understand and experiment with those methods, or potentially incorporate those techniques into my own work. For that reason alone, I almost think I have to look at other work. There are absolutely great artists in LA, but then for each one of those, there are 40-something knockoff kids that are somehow also making a living remixing their own version of the hit song. There have always been great galleries in LA too, but I don’t feel as though there’s the same level of criticality that would force artists working here to perform to the standards they would have to in New York. There’s also an intellectualism built around art in New York and London that doesn’t quite exist here.

My wife loves art as well. From an early age, her mother would take her to the theater, and to see exhibitions and museums in New York and London. She has such high standards because of that, and keeps me from going to bad painting shows.

CG: *Laughs* That’s amazing.

CC: For sure. Not to say that I don’t sneak off sometimes just so I can show support, but her criticality has become vital to me.

CG: Thinking about New York, I was looking through your social media and noticed that Jerry Saltz seems like quite a fan…

CC: I’ve never had any interactions with him, but he occasionally likes something I post on Instagram. I don’t think Jerry Saltz has the time to look at work created by straight-white-male painters, you know?

CG: I’m sure there’s no way he could avoid it though.

CC: But current conversations have been so far elsewhere, and I am fully aware that I don’t fit into certain narratives, and that’s ok. Roberta Smith came and saw a show, but didn’t write anything. We spoke a bit, it was a gnarly show. The show inadvertently revolved around my mother, who was such a huge victim to conspiracy-theory mentality. It also poked at edgelord-y propaganda that was rampant in the lead-up to Trump’s first presidential term. The accompanying exhibition text didn’t make any of my intentions with the show very clear. It was more of a poem.

Let me pull out a painting from that show.

Canyon and Birdie with, Bad Actors, The Video Game, 2019, oil, acrylic, and spray on canvas, 80 x 60 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CG: Charles Manson!

CC: Here’s a funny story. In 2023, I pulled this work out for the first time in years. Unboxed it, hung it up on the wall, and Henry Kissinger died the next day.

CG: Spooky… he must have been 100 years old.

CC: Yeah. The most requested villain of all.

Canyon Castator (b. 1989, Houston, TX) makes large-scale paintings that satirically address our social reality, bringing together an exuberant blend of figures culled from the internet, modern media, politics, and personal experience. Castator’s world is hyperbolic, saturated with dissonant characters, knowing symbolism, and distorted narratives. His distinctive aesthetic is not tied down to one language but fuses digital and traditional mediums in a cacophony of psychedelic vibrance.

Castator’s work has been exhibited internationally and is held in private and institutional collections across the United States and Europe. Recent exhibitions include Diane Rosenstein (Los Angeles), The Hole (New York), Carl Kostyál Gallery (London/Stockholm), and Plan X (Rome). His work has been reviewed in Bomb Magazine, Juxtapoz, Artnet, and more. He is represented by Carl Kostyál.

In addition to his studio practice, Castator is the co-founder of Mohilef Studios, an artist-run studio project in Los Angeles. Through Mohilef, he continues to foster community, experimentation, and collaboration within the contemporary art landscape.

Clare Gemima regularly contributes to publications such as: Painting Diary, Eazel, Impulse Magazine, Artefuse, Contemporary HUM, Art New Zealand, Brooklyn Rail, Two Coats of Paint, Whitehot Magazine, EV Grieve, AWT, Wide Walls, Frieze, Passing Notes, New Women New York, and Artsy. Her work focuses on building scholarship for immigrant artists pursuing their artist visas, as well as emergent, established, and historically overlooked practitioners based in New York and abroad. Her work has allowed her to travel across the United States and internationally, where she has reviewed exhibitions and interviewed artists showcasing at esteemed galleries, archives, museums, and fairs, including Untitled Art Fair (Miami), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh), New Museum (New York), Honolulu Museum of Art (Hawaii), and the Venice Biennale (Italy).