In conversation with Andrea Zabric—Binding Time

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Graphite Series, No. XVI), 2023, pigments and binders on MDF, Ø 140 cm. Photo: Serena Schettino.

“…I’m not a painter who has a plan of how the painting should look, which totally contradicts how fresco works. Because you need to have a day’s plan if you want to create a fresco. So I guess I wanted to test myself—it’s almost like building an obstacle for oneself, in terms of technique and to see how it changes.”

—Andrea Zabric, 2025

This conversation between painters André Hemer and Andrea Zabric traverses her move from Ljubljana to Vienna, her experience of academia there and finding her own painting practice.

Now largely based between Vienna and the Karst region of Slovenia, Zabric manifests her paintings through a material conversation with the natural environment. Imbued with an abundance of rich and tactile surfaces, they are artifacts that hold a mirror to their place of creation and offer a painterly encapsulation of a day’s experience.

Here, Zabric gives insights into the unique nature of her studio setting, explaining how this sensory and spatial experience deeply informs her work. Shaped by time, light, and tactile experimentation, she makes work that moves beyond the static, creating objects that are both shaped and changed by their place in the world.

This conversation also marks the first in a series of curated exhibitions hosted by Painting Diary in partnership with Vienna-based curator Alexandra Toth. The exhibition, entitled Day’s Work, takes place at Painting Diary in Vienna between November 14 and December 18, 2025.

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between André and Andrea which took place at her Vienna studio on October 10, 2025.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Karst Series, No. VI), 2025, fresco and various media on birch plywood, 144 x 110 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

André Hemer: Hi Andrea. So we’re here at your studio in the 18th district in Vienna. You were born in Ljubljana, Slovenia—did you grow up there, too? And when did you first come to Vienna?

Andrea Zabric: Yes. So I grew up in Ljubljana but I moved to Munich when I was eighteen to study art. Not because there weren’t any art schools in Slovenia, but because if I had stayed in Ljubljana I thought I knew what my life was going to look like. Slovenia is actually similar to Austria—you have one big city and the rest of the cities are smaller, so it’s very centralized. And somehow I didn’t like the idea of that, I didn’t want to make art where I knew what it was going to look like. It’s like with images, it’s very similar—I always think that if you already have an image in your head, then this is not the image you use for your paintings, because it’s like, then it may need another medium. But painting isn’t the right medium for finished images, in my opinion. So anyhow, I went from Ljubljana to Munich to study, and then I also studied art history and philosophy because I was unhappy with the discourse we were having in painting at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. It was formalistic.

AH: Yeah. So I noticed that in your biography, you did your diploma at the Academy. And then you went and did the BA in art history, and then you went back to the Academy for your Master’s?

AZ: Exactly. I came to Vienna in 2019 and did my Master’s here. It was a mixture of art practice and art criticism or theory, or… like… just a practice in thinking. Maybe this is something I was looking for for a really long time. Which language do we use when we talk about paintings? And I don’t have, like, a recipe or something.

AH: It’s interesting. I think that with art schools everywhere they can become quite insular with language and the words spoken to describe things. And so they often become a bubble of their own. And that mode of criticality is then reinforced. So I think it’s good to step away and put your headspace somewhere else to reframe that.

AZ: Yeah. I mean, I didn’t do anything radical—because I did art history, which is even more, let’s say… rigid!

AH: Sure. But you have to find the formalism to break the formalism!

AZ: Something like that.

AH: When you were doing your diploma, was your frustration at the lack of criticality about yourself or about the class as a whole. What was the dynamic there?

AZ: I learned the most from my peers. I think it’s the everyday where all the knowledge somehow circulates: hanging around in the studio, drinking wine in the evening, smoking cigarettes, and of course, during the day, attending all the things you have to attend if you want to actually develop your work. It was also very valuable to talk to the professors, don’t get me wrong, but I mean, they appeared every now and again, and it was, you might say frontal, you know, you present your work, you try to talk about your work. But you don’t find the words for your work. Everyone wanted to talk around the problems, never really addressing the problem in a painting. So I think we were avoiding the elephant in the room. And it was always a different elephant for me or for another student. It’s not that we were too gentle, but we didn’t nurture the culture of criticism or critique as a mode of thinking.

AH: That makes sense. And often the elephant in the room is the painting itself, speaking to the object that’s in front of you, rather than everything outside of that thing. So you did your BA in art history and then you went back and did your Master’s at the Academy. Was there a shift then, when you went back?

AZ: Yes. Because then I was among people who were not painters and didn’t know how to talk about painting in the way I was used to talking about painting. So you had to adapt to the language. And to find parallels to something that they were doing. This was also the moment when I started writing about painting. Before I didn’t do that, it was always a separate practice. And then I noticed that every painting can produce its own text or language, or not. And that’s what I was trying to do in my Master’s in Vienna.

AH: And since finishing you now split your time between Vienna and Slovenia?

AZ: Yes. And sometimes I also visit Munich because I work at the Museum Brandhorst, where I do art mediation, like educational programs, which again brings me back to this language–image connection.

AH: Right. So wearing different hats and thinking about things in different places and spaces. Let’s return to where we’re sitting in your studio. There are a bunch of paintings here, and as you mentioned before we started recording, they’re at different states of being. Some are finished, some are in the midst of being formed. The processes in them seem varied.

For me, though, the biggest thing is the surfaces—they’re all unique terrains, so to speak. And I was thinking about a karst landscape in terms of geology and porous rock types and the mattness of some of your surfaces. This mattness comes from something that’s porous, and this also relates to some of your fresco processes, where pigments seep into the surface—and in the end it’s a very integrated object of pigment and material. But then other paintings have finishes that are glistening as if they have a shield over them; holding all that matter in. Do you want to speak a little about these different approaches?

AZ: I think you made this observation about the surfaces, which is the first thing that pops into our eyes, because I am trying to address different operations in a way. You might have a classical fresco technique, but it’s not directly on the wall, but on plywood, like the rest of my paintings. In all the paintings the carrier of paint is wood; wooden panels made of MDF or other kinds of wood. So there is also a possibility that I paint directly on the wood or in some cases the Intonaco of the fresco.

Andrea Zabric, detail of Untitled (from the Karst Series, No. III), 2025, pigments, flowers, and binders on birch plywood, 34 x 34 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: And what’s the exact process?

AZ: It’s created from a mixed plaster which is already fluid, but it hasn’t reacted yet. And then you need to collect different sorts of sand, like different granulates. It should be very, very fine, but also a little bit rougher—it’s like when you’re building a house or church and you want your walls to have structure, because then the paint is going to stick. So it has to be a very physical thing, a fresco.

At first, you have a thin, rough layer; arriccio is the proper term. Then it has to dry and then you have to wet it again, before you apply the next layer. It has to be moist as you apply the intonaco, which is the layer you paint on. And this intonaco has to be fresh, but of course you can also add something afterwards and it would be alright. So basically, my paintings here are a mixture of fresco and secco.

But I’m not a painter who has a plan of how the painting should look, which totally contradicts how fresco works. Because you need to have a day’s plan if you want to create a fresco. So I guess I wanted to test myself—it’s almost like building an obstacle for oneself, in terms of technique and to see how it changes. What does it change? Because something changed, for sure. But I wasn’t really sure what was going to change in the process.

AH: And how long do you have available to work in that first shot with the fresco?

AZ: I would say two days, because you have different tricks in terms of how it stays moist or fresh. Every two hours, you have to cover it with some wet piece of cloth or something, but not for more than two days. I would say after two days it’s dry, especially in summer.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Karst Series, No. II), 2025, fresco on birch plywood, 40 x 28 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: Okay. And from there, some of the paintings might stay in that state and some of them might develop into something else? But where does that decision happen? Is it in the moment? Or is it something that’s longer and more expanded?

AZ: Yes, but it’s like you don’t really know how long that relationship with the painting will be.

AH: That’s a universal.

AZ: True, like a very nice short affair. And then the painting is there, and then there is nothing we can say to each other anymore. And sometimes it’s like a troubled long relationship, which is also beautiful and important. But it takes some more time. And I would say there is chance and circumstances around this. What does it mean that a painting is finished? I cannot really say that there is a recipe I follow. It’s a very in situ decision that I’m making.

AH: Yeah. And it’s almost like the painting then needs to find its own objecthood. It’s finding itself and you’re sort of along for the ride in a certain respect.

AZ: Yes, that’s how I think of it.

AH: Something else I was thinking about when seeing reproductions of your work, was that the image probably has nothing to do with what you want to do, and yet there’s still something formed there. And I wonder if that’s anything that you reflect on afterwards, per se? I know that you’re not trying to find an image, that’s not the starting point or direction. But there are certain continuities between work where there is something happening—and I won’t say that it’s anything figurative—but they become something that might be about landscape or even some of the materials that you’re using.

AZ: Yes. I think it has many provenances. Sometimes, as you said, the material creates an image, like grains of pigment create something like an image. We could say that an image is like different fragments of my, let’s say, everyday studio life. Obviously not part of the studio reality, but traces of something that I’ve seen or that has followed me inside.

AH: Yeah. And I’m actually just noticing that there is a structure in this painting down here which has a gridded system, these horizontal, vertical lines. And here, a blue line that traces through this oval painting, which is almost like a river.

AZ: Exactly. Sometimes I need things that I can grab onto. So I put something in that I can define. This is this. And it plays at a level of representation. As you said, this can be a river, this can be an apple, this can be a flower, or something. But it also gets another function in the painting. So it’s maybe a river, but when it becomes a part of a painting, then I think it’s a threshold between many particular things.

Andrea Zabric, detail of Untitled (from the Karst Series, No. I), 2025, fresco on birch plywood, 40 x 28 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: Yeah. I think that part of my observation was seeing those paintings in reproduction has a different scale to a real life experience, seeing things firsthand. The imagery definitely recedes, and the thing that is first and foremost is the tactility, the surface, the objecthood of what you’re seeing. And that’s the thing that is the thing.

AZ: Yeah. Sure, sure.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Umbra Series, No. VI), 2024, pigments and binders on birch plywood, Ø 24.4 cm. Photo: Serena Schettino.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled, 2024, pigments and binders on birch plywood, Ø 24.4 cm. Photo: Serena Schettino.

AH: And then also in terms of format there’s a varied collection here—there’re a few oval pieces, there’s a little tondo, and the rest are squares. How do you decide on those formats?

AZ: I mean, these are my, let’s call them, cabinet formats. I like squares and tondos because they’re somehow coming from another world—it’s like mathematics or geometry. It’s not rectangular like a portrait. Vertical or horizontal formats automatically have something to do with being an image, being a landscape or being a portrait. So I wanted to avoid this and I decided on a square, which is almost like looking at them right now, it’s like they can all be like a fragment from a larger picture. And with the ovals, I like this distorted tondo moment, because it’s a circle but it’s not perfect. And it has a lot of connotations. I always think of a mirror or baroque or the way that planets move around, like in a solar system and so on. So nothing is really perfectly round except in our math mind. An oval is somewhat more organic.

AH: And not to make too strong an allusion, but I know that you’ve exhibited and worked in Italy. And I imagine there must be a connection there to painting in an art historical context, and to modes of making in that way?

AZ: I do feel very much drawn to this language of painting. So we didn’t address this large piece in the studio, which is part of a series of fragments that look like theater props that are actually directly taken from Pompeii wall paintings. They were used for an exhibition I did in Zagreb, and luckily I didn’t use them in the same way for an exhibition that I did in Naples, because that would be somehow, a bit tautological. In Zagreb I used them primarily as a background for my paintings. So I would actually place a smaller painting on this fragment, which is almost as tall as I am—so quite a big piece. It would be like a prop, and then a painting on top. This is still something I want to investigate, because these perfect white walls and light systems, I think this is a bit passé in a way. It’s not something that interests me. I think I can look and engage and invest in the painting without the white cube and all these things, right? It can be differently, how to say, staged?

AH: Exactly. And it’s sort of ironic too, because painting can be so heavily staged in its making, and sometimes there’s a dishonesty in terms of how the conventional gallery space wants to strip that back to this neutrality which is sort of impossible. Neutrality just becomes its own thing, its own language. Have you created shows where you’ve worked in more unusual spaces, or made work in response to a space?

AZ: Well, different galleries have different spaces. It’s not that I make paintings for that space, but when I know which space I’m exhibiting in, then I try to think, what do I have to do with this space? So it can facilitate my paintings in the best possible way. I wouldn’t say it’s so site specific, but it is responsive.

Andrea Zabric in collaboration with Bernt Preisegger, Untitled, 2024, pigments and binders on birch plywood, approx. 150 x 95 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Karst Series, No. VI), 2025, fresco and various media on birch plywood, 140 x 95 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: Okay, so extending the idea of space, I wanted to talk about the fresco process being a one-shot thing, but you also work outside in the environment. And are you actually painting outside? What is that process?

AZ: Yes. I think the most special thing about these paintings is that they are mainly made plein air. So there is bird shit on them, and there are a lot of small moments where you can see the traces not only of the artist’s hand, but also of the environment. Sometimes I leave some leaves or flowers or dust or even parts of dead insects that fly in because they find it so attractive to go into the shellac and all the other stuff that is completely dangerous and they…

AH: …they die a beautiful end!

AZ: I hope! So working plein air, I think it’s one of the best experiences I have in painting. It’s something I thought, but why? It’s such a classical thing. You have to pace yourself to the time of day and the weather. And so I have different protocols or regimes that are not necessarily set by me, but by the material and the logic of the material. What does it need to do that and that? Or like the days and hours and weather and all the things that I cannot control. It’s actually so much about not being in control or taking control at a certain point, it’s like something you cannot really exercise in everyday life, right? Like in relationships, for example.

AH: Exactly. I also have a lot of empathy toward that process, and I think that there is something interesting about finding a beginning from outside of yourself. And then it really is this conversation between you and the materials that you’re working with to manifest something. And it’s not always going to work out.

AZ: So yes, as I already addressed, it’s this moment of chance and of things that are happening without your control. It’s not that it’s arbitrary. In the end, you decide what stays and what doesn’t. It’s taking advantage of all these everyday situations or the cosmic forces around you. It’s something that painting definitely can facilitate as a medium.

AH: Perhaps we can speak about the Painting Diary collaboration with Alexandra Toth—a gallerist and curator based in Vienna and someone you’ve worked with for a little while, right?

AZ: We have been in conversation now for a year. We did an art fair in Marseille together, and I think she was following what I was doing for maybe a bit longer. But to be very honest we didn’t talk much directly about paintings. There is still space for that, to talk about what is happening in a piece.

AH: So you’re doing an exhibition in the Painting Diary space entitled Day’s Work. From our conversation thus far, I think it’s clear where this title comes from, but perhaps you can expand on that within the framework of what you’re going to be exhibiting?

AZ: I think I revealed a lot already in the answer before about the process—what can happen in a day? But usually I like to title my exhibitions as a female figure somehow, either in the background or as a subtext—for example, Ada, Palmina Zima, and Afra Sperantia. As if some of them were real and some of them not, like imaginations. And they were ghosts that I needed to put together—you know, all the pieces. And now something different happened, this situation of working outside in this very beautiful spot. Somehow I didn’t need any additional ghosts, or I didn’t need a kind of epilogue or prologue to the show. Because the paintings are already full of ghosts that you can trace, which wasn’t as possible before.

I’m going to show some of the four smaller pieces that you see here and there will also be four larger fresco paintings, also ovals. The large ones are actually a compound; so sometimes on one panel a fresco meets another technique, which is kind of a nightmare for all restoration because I do everything wrong and I make my own recipes. A fresco is something that stays for a really long time, that’s its aim, but my paintings don’t have this agenda, to stay there forever as an image.

Sometimes I decide that in one show, a painting will hang this way; and in another show, it can hang, like, upside down. So it’s modular. That doesn’t mean that everything goes with everything. But I think that they are resilient and adaptable to different situations to a certain degree. It’s not something that is really fixed, you know, even when it looks frozen. I like that there is a frozen moment of moving in the painting. But it’s not really frozen, if you take your time and look at the painting for longer you could see it as moving and functioning as a fragment from something larger.

AH: Yeah. I like that idea—that when you’re dealing with a body of work that is made in the same place or same time span, that they are all fragments of one another, just by their very nature. That’s something that we don’t often give enough importance to when we confront or talk about an exhibition: that the exhibition is also the whole, it’s all connected. And were the large works in the exhibition made in Vienna or elsewhere?

AZ: They were also made in the house, in the Karst region in Slovenia. So all the works that are going to be shown at the Painting Diary space were made there.

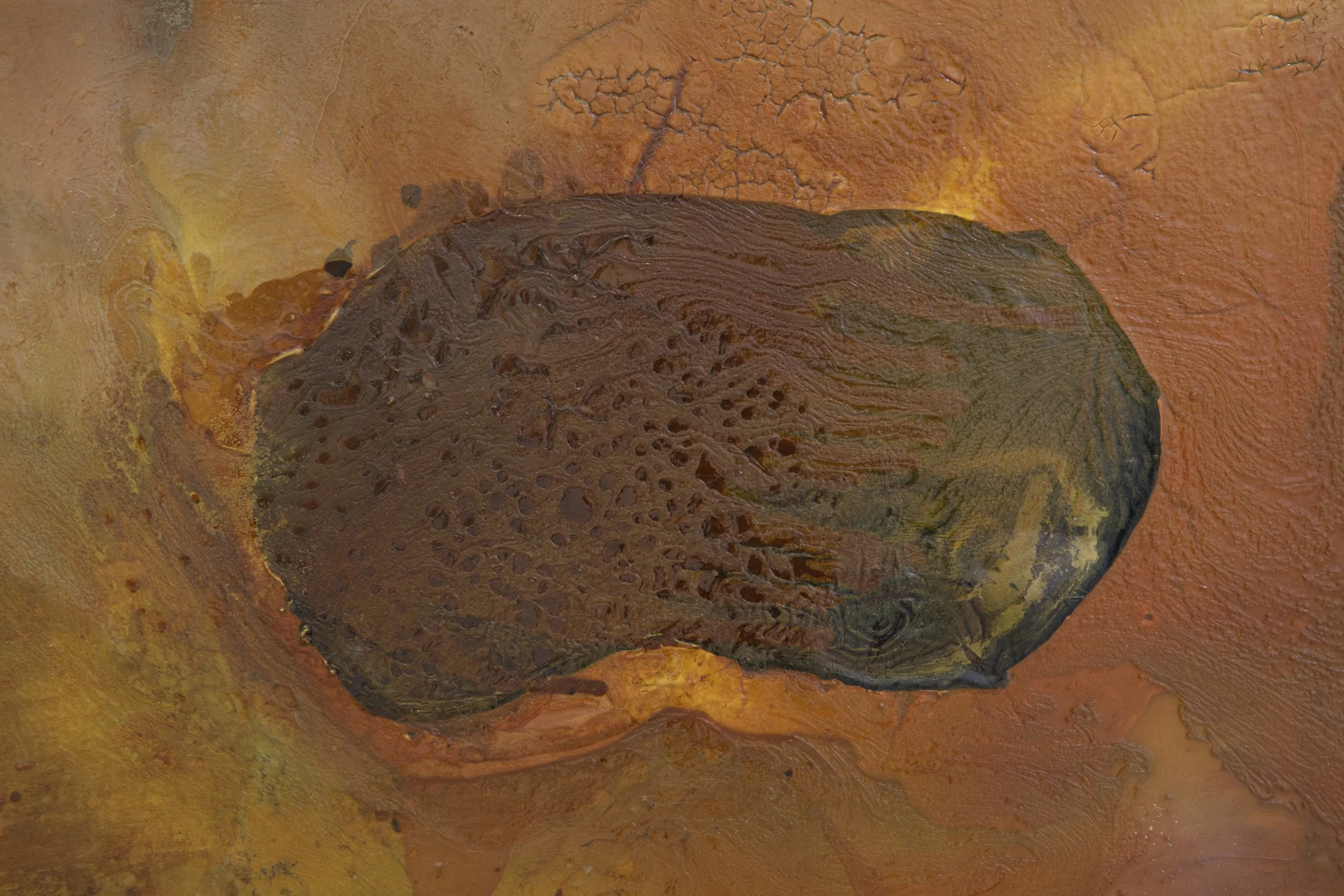

The Karst studio in 2025., From the artist’s archive. pigments and binders on MDF. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: Can you describe that house and studio and where it sits in a landscape sense?

AZ: Well, it’s a typical Karst house, which means it has a yard inside. It has walls all around, so you’re actually working in a very safe space. You enter, I think you would call it, an atrium. Karst is a region that is basically made out of limestone. And it has a lot of wind and all the water that is there is underneath the ground. So there are no rivers, there are no lakes. There is the Adriatic Sea, which is 15 or 20 km away. You can feel it, but you cannot see it. So I think that’s a very special situation. And I feel this house is protecting me from all four sides, so I can move there very freely. I have my own space; the house, yard, and atrium. And it’s at the end of the village so I don’t really see neighbors, but there are a lot of beautiful trees.

AH: And do they ever come into the work in a material way?

AZ: Things that I really love or admire to that degree, I wouldn’t incorporate so directly into my paintings.

AH: Right. Coming back to the paintings, I’m here looking down at the marks on the studio floor. And I had an intuition that you probably worked with the paintings down on the floor. Is that the case or does it change from the beginning state to the later stages?

AZ: It’s both actually. I always like to compare it with sleeping, standing, and sitting. It’s like it’s changing positions all the time. But yes, this liquid situation happens, of course, in a horizontal position. But between, you always have to put it on the wall, because that’s how it’s supposed to be. And I don’t exclude the possibility that in a show I would use the floor as a wall.

AH: Yeah. I think this also relates to what you mentioned before, a painting could be one way in one show and then maybe flipped in another show. And that, for me, rang true in the sense of like, when you make things that are very much objects, and so there’s also a sculptural intuition that goes into that making.

AZ: The light changed since we were sitting here. I think that’s also an important moment. I had to do a show once that opened in April, which meant that I did all the production in winter time. And the days in Vienna are really short. And if it’s raining, they’re even shorter. You’ve seen how dark it was 20 minutes ago. And now there is much more light and all these things kind of matter in the process.

Andrea Zabric, Afra Sperantia at Galerija Kranjčar, Zagreb, 2024. Photo: Juraj Vuglač.

AH: Yeah, extremely so. It completely changes the way you look at a painting, because of the way the light reveals the surface. It actually reveals the making of the painting. Whereas the two paintings here—one has a very strong glossy surface, the other one is completely matte. It’s so interesting seeing them in relation to each other.

AZ: Yes. I think there’s a lot about oppositions, forces that are against each other. Like in this painting with these transparencies where you can follow every layer. But with fresco it’s not like this—because when you cover one layer, then it’s covered. You can have a feeling that there are many layers behind, but you cannot really see them. So either you imagine them or maybe somehow build yourself obstacles or maybe question marks or just like an experiment while you’re working. I think that I get bored very fast, as a person, and in painting, I cannot stick to one thing for very long. Even if it means that there is a certain degree of dilettantism in the work, you know. But you use this to your own advantage—or when you use it and why you’re using it becomes an addition to the process.

AH: Some of these paintings, they look like they’ve been worked back into, like an erasure of the surface is happening. Is that the case or is that purely a result of the layering? I’m looking especially at this one down on the floor here and also this small oval work.

AZ: Yes. The reason why I started with wood panels is because sometimes I want to remove things completely. I could sand the surface, which is not possible with a canvas. And the canvas has this space between the canvas and the wall. And it doesn’t work for me. So I need a hard surface, where the materials can sit and where I can press with my hands against it. And if you put it very plainly, I think there are two main operations in these paintings: adding and removing. And how these happen is a question of technique. Very rarely do I use a brush, even in fresco paintings. I use my fingers and my hands and cloths—but very rarely a brush.

Andrea Zabric, detail of Untitled (from the Apennine Series, No. II), 2024, pigments and binders on birch plywood, 177 x 125 cm. Photo: Serena Schettino.

AH: And in the works that have this glaze-like quality to them—what is that materiality? Is that just a finishing layer, or also a device to move pigment around?

AZ: It has different functions of course. But for me, it’s to seal something, as in the works of Dutch Renaissance painters. They would glaze their paintings at the end with damar, gum arabic or shellac. And it’s like a moment when you freeze the painting and say, “Okay, that’s it.”

AH: And it binds it into one.

AZ: Yeah. And sometimes it’s just in order to move the pigments from one side of the painting to another, which we didn’t actually address—that’s another technique I use. Here it’s not so present except in one painting, but it is present in the larger ovals using encaustic—putting pigment in wax. It’s interesting because it’s also a technique that has to do with timing.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Apennine Series, No. 0), 2025, encaustic and various media on MDF panel, 35 x 35 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

Andrea Zabric, Untitled (from the Facade Series, No. III), 2025, pigments and binders on MDF panel, 42 x 28 cm. Photo: Andrea Zabric.

AH: Exactly. It’s very time limited. Even more limited than fresco.

AZ: Yeah. So you have to always add heat in order to form the wax. And it also has a completely different texture, like this matte part in this painting.

AH: It’s a very specific kind of surface, like a fabric being folded and compressed.

AZ: Yeah. There is something also very brutal in this painting. A lot of cracks, a lot of moments that are like separations. And also the edges, how one surface meets the other. It’s not really, how to say, tender.

AH: It feels very broken. And one thing is exposing another thing.

AZ: Yeah. The encaustic and fresco, both have to do with these limitations that come from outside, from material, from different sources.

AH: One thing I like to ask any painter is about the edges of a work. For any painting, you understand so much by looking at the side of it and how it’s come to be. And I love that in so many of these works there is a real fragility and tenderness about those edges. The parts that I assume are part of the fresco process, seem to be almost dangling off. And yet they’re all different. Every painting here has a slightly different dirtiness or construction about it. And then these two square paintings actually have a framing as well.

AZ: Yes, these have framings. These are the paintings I worked on for several years. I mean, not every day, obviously. They’re each 34 by 34 cm. And actually, I was really disturbed by the frame. But I wanted to try, because these started as a copy, as an exercise. So I would go to a museum or I would have a reproduction and I would just, like, try to see if I can do it. Because then you understand how the paintings are made, you know? It’s the logic behind it. And here it was actually two pieces of a wall in a kitchen in Pompeii. Only a little of the remains of this kitchen are still here. And I thought, okay, this needs a framing. It says, “I’ve been in a house.”

AH: It was domesticated?

AZ: Exactly. That’s a good word for it. Alexandra actually really likes these two paintings. I’m not such a big fan of them. They were also finished at the house. Now there is nothing else I can say to them, which sometimes is not really true. There are some moments that I almost recycle my paintings, although I hate this word in the context of painting. But it can happen that in five or six years’ time, I would go back to a painting or and I would put another layer that would somehow mark a start of a new life for the painting. For example, I can imagine that these two paintings will be something else, in twenty years maybe.

AH: Do you ever destroy paintings or do they all just exist in that process you described and maybe find a new life?

AZ: Not really. They always get used. I use parts of the paintings in different kinds of ways. And now, I am having a little show in Ljubljana. I even used some pieces of my paintings and I put them into the furniture. So I wouldn’t say that I destroy them… maybe I do destroy them in a certain way, but they always find their way back to me somehow.

AH: And relating to your degree in art history, do you continue to write outside of your practice now? And how does that percolate into what you do, in terms of painting and beyond.

AZ: I got a really nice compliment from a friend of mine about this recent exhibition in Ljubljana, where there is just one painting, the rest of the objects are not traditional. And he said, I see that there is a painting logic in the show, although it’s not a painting show. So when I write, I write like I paint. And when I write in the context of art, I always adopt a text or language for the audience—this is meant to be the biggest challenge, but for me the nicest challenge is to find the language, maybe for people who are not from our media, because that somehow forces you to rethink some things, like abstraction, what is that? I mean, that doesn’t mean anything to my mother, a child, to anyone who is outside of our profession. But I wouldn’t say that I have a writing practice that is equal to my painting practice. It’s parallel, but it’s not as influential as the painting.

AH: Right. It still comes back in a way.

AZ: Yeah, exactly. And just like art history and critical studies, they equipped me with tools that I need for discourse. I don’t understand myself as an art historian or an art critic, although I write about art and publish things about art. I’m still just a painter.

AH: That makes sense. So the opening for your exhibition Day’s Work is on November 14. And we’re very excited to be hosting you and Alexandra in the Painting Diary space. Thank you so much for taking this time to talk to us.

AZ: Thank you, André, for all the good questions and for hosting the show in the studio.

AH: You’re welcome.

Andrea Zabric (b. 1994, Ljubljana, Slovenia) is a painter who writes about and through her medium. Her practice develops from the reciprocal processes of making and encountering images, extending from compressing pigment powder and designing work garments to scripting radio broadcasts, developing educational programs, and creating painterly installations. Central to her work is an exploration of the ontological and embodied dimensions of painting, informed by feminist and psychoanalytic approaches and attentive to the interplay of material, gesture, and perception.

She graduated in 2018 in Painting and Graphics from the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and in 2019 completed an undergraduate degree in Art History and Philosophy at Ludwig Maximilian University. She earned her Master’s in Critical Studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna with the project Painter-Antenna. Andrea Zabric has presented her work in five solo exhibitions and numerous international group shows, including at LFA in Naples, the Kranjčar Gallery in Zagreb, and Salzburger Kunstverein. She lives and works between Vienna and the Karst region.

André Hemer (b. 1981, Queenstown, New Zealand) is a New Zealand painter based between Vienna and New York. His work investigates what it means to create paintings during a time in which we are continuously moving between states of physical and digital experience. In addition to his studio practice he is the founder and lead editor of Painting Diary.

His work has been exhibited at Taiwan Museum of Art (Taipei), Total Museum (Seoul), Münchner Stadtmuseum (Munich), and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Awards and residencies include: International Studio and Curatorial Program, New York (USA); The Studios at MASS MoCA, Massachusetts (USA); the New Generation Award, Arts Foundation of New Zealand; and the National Contemporary Art Award, Waikato Museum (NZ). His work has been featured in publications including 100 Painters of Tomorrow, published by Thames and Hudson, and Art and the Internet, by Blackdog Publishing.

He undertook his MFA at the University of Canterbury (NZ) and completed a post-graduate research residency at the Royal College of Arts, London. He also holds a PhD in Painting from the University of Sydney.